ABOUT THE PROCESS

OR ‘BUILDING A DIGITAL FLEET’

By Michael Brady

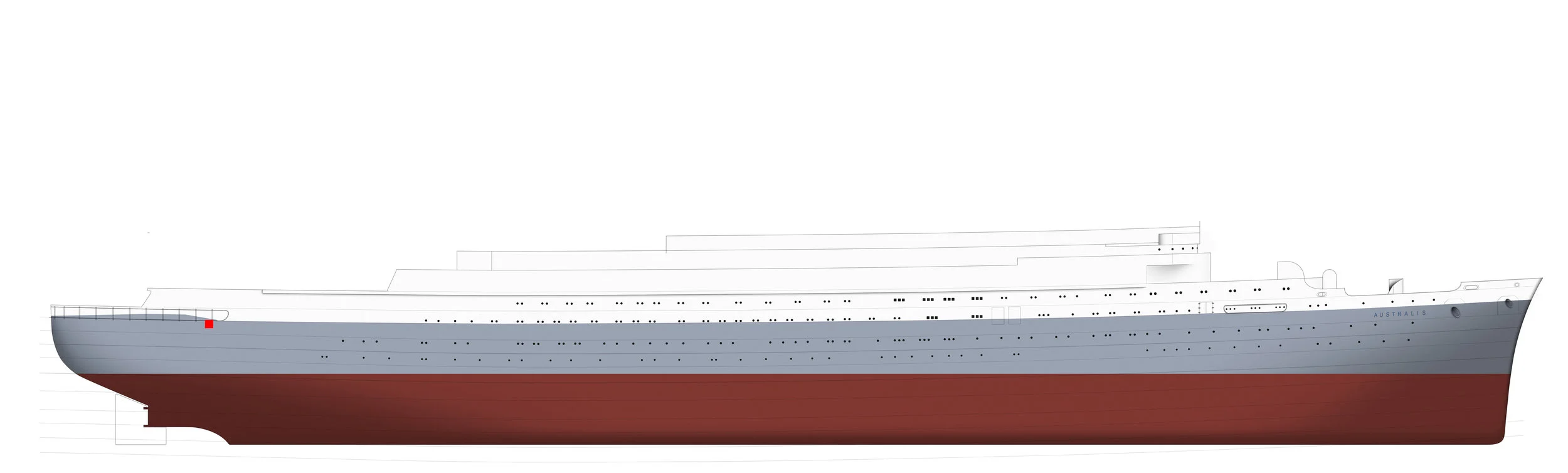

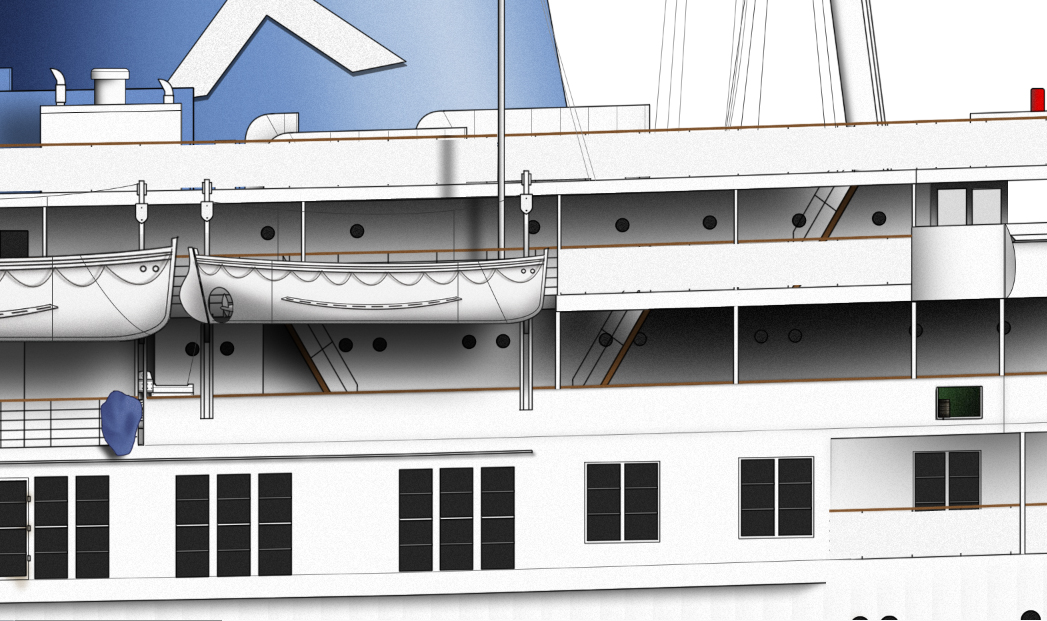

TSS Strathnaver - reality at left and the Liner Designs illustration superimposed at right.

In their day, Ocean Liners were the very pinnacle of mankind’s technological success. Although most have since been relegated to the scrap heap and the pages of history books, today they can be remembered by making use of the technical marvel of our common era; the computer. I’ve set about completing colour technical profiles of ships both famous and obscure, from the most luxurious Transatlantic liners to the most Spartan of Australasian immigrant vessels. Please enjoy this brief explanation of how I set about building a digital fleet.

COPIOUS AMOUNTS OF RESEARCH

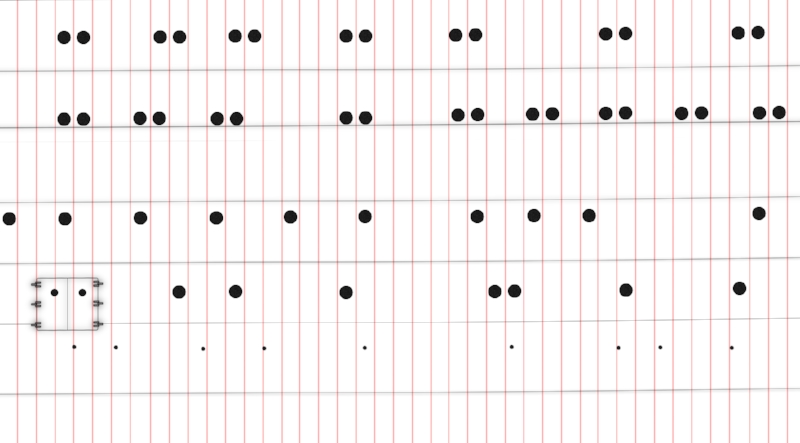

Often, plans like this one give a general sense of the ship’s shape and proportions but are totally lacking in detail.

When blueprints and plans are unavailable, hand sketches based on photographs help to clear up the complex structures of the ship before I begin drawing it on the computer.

Before drawing can even begin I need to accumulate a massive amount of research material in order to make the drawing as detailed as possible. One would think that blueprints would be the most useful resource, and in a general sense they are, but photographs are usually the most helpful. While blueprints will show a ship as she was at launch, they will generally lack any detailed representation of, say, the myriad types of vents and fans and other 'deck clutter' which littered the public spaces of those ships of old. (Any former passenger will likely remember machinery and coils of rope scattered about the decks.) Not only this, but many original blueprints are either locked away in the vaults of private collectors or simply no longer exist - For example, when the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast was bombed during the Blitz, thousands of original blueprints and plans were destroyed by fire, including those of Titanic and her sisters.

PHOTOSHOP - THE MARVEL

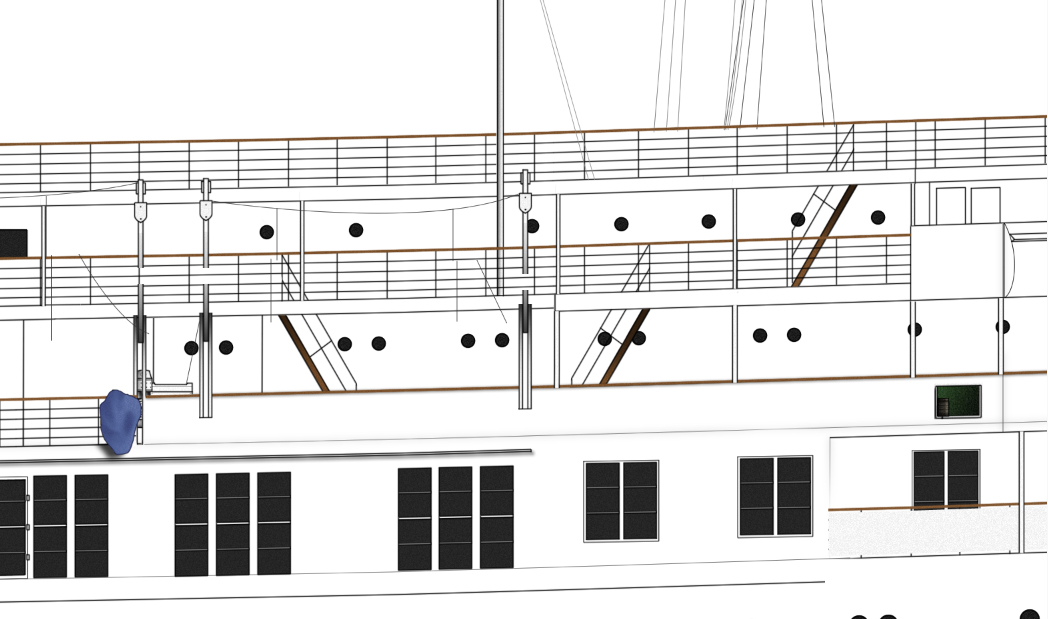

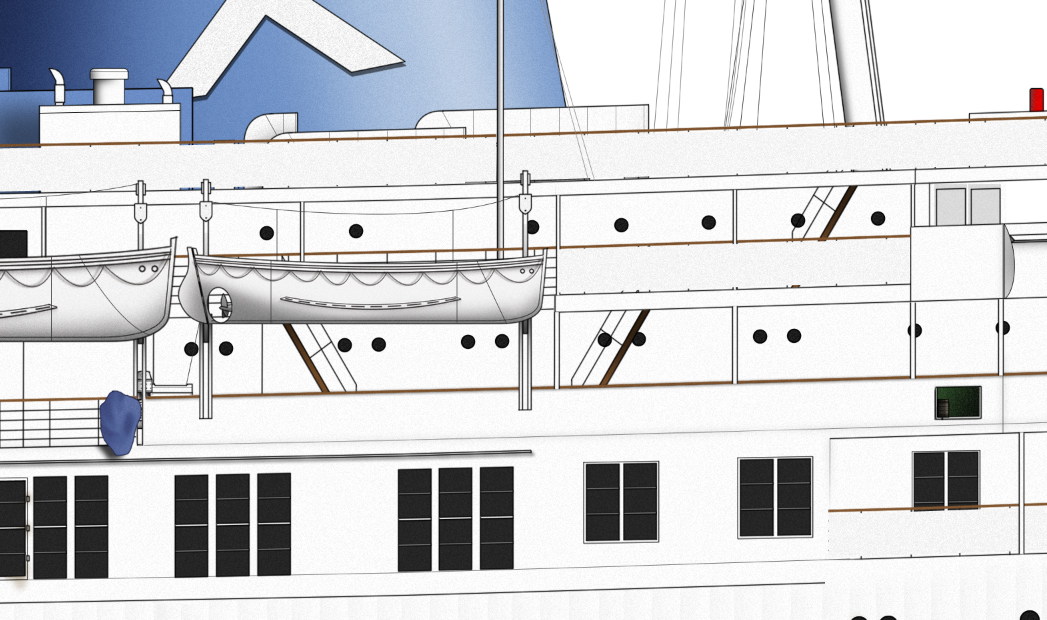

After a few days of drawing, the vessel’s basic shape is complete and I can begin placing doors, portholes and hull plates.

Here you can see how portholes interact with the ship's Frames. The Frames (Red lines) act like the ship's 'rib-cage' and in reality shipbuilders would cut portholes between them. Temporarily adding them to my drawing ensures I can place the portholes and windows with a degree of accuracy. Once the portholes are correctly placed, the 'frames' are deleted from the drawing.

After a big collection of photographs has been assembled, it is time to begin drawing. Photoshop is my preferred program - primarily used for manipulating photographs, it is also a very powerful illustration tool thanks to the inclusion of a number of useful functions. Just like a real shipyard I start with the ship's keel- her back-bone - and work my way up including hull plating and frames. The frames act like the ribs of a great whale, spaced about 30" apart down the entire length of the ship's hull. Including these in the early stages of the drawing means I can accurately block in the location of portholes and shell doors which typically were placed in the space between frames.

Photoshop is a program that works in layers, almost like a stack of drawings completed on clear plastic sheets aligned atop one another. With the outline at the top, I can begin to colour the drawing behind it, starting with the hull's basic colours in solid blocks - usually red for the waterline, black on the hull and white at the superstructure - and then build up, with more layers, shadows to highlight the hull's curvature and rust to create a more realistic-looking drawing.

A ship is BORN

Some days later and the hull is complete - now the complex deck structures and passenger accommodation can be ‘built’ on top.

Windows are added all along the superstructure and the deckhouses are roughly outlined and coloured - it is the shading that makes the structures look 3-dimensional. I think a ship doesn't really look like a ship until she has her funnels - these are added atop the superstructure along with any other large structures like masts and cranes. Although it might now look like a ship, the drawing is lacking those things which made those big old liners functional ocean giants; the aforementioned 'deck-clutter'; electric winches, bitts, capstans, bollards, lifeboats, davits, fire hoses, piping, ventilator and fan cowlings are studied, emulated from photograph, and included on the drawing. This is the most challenging process since many of these smaller details are almost impossible to distinguish in photographs. Educated guessing and a degree of artistic license is sometimes required when photographs just aren't enough! Including these details is important for reasons other than being able to tout about 'detail' - some former passenger might have a long-forgotten memory tied to any piece of equipment from the deck of a ship and seeing it on the drawing just might be enough to trigger it!

A week or more of drawing and the ship is ready! In this case, the SS Australis of Chandris Lines.

Much of the challenge of this form of maritime illustration comes, not from the drawing process itself, but in interpreting grainy old photographs and depicting ships, not as they appeared in blueprints as sterile engineering projects, but as they appeared in life; lit by the sun, rusted by the ocean and well-lived-in by their occupants. If someone were to look at one of my drawings and feel the same sense of excitement or awe they might have felt seeing the ship in reality for the first as a child then I would be a happy fellow indeed!